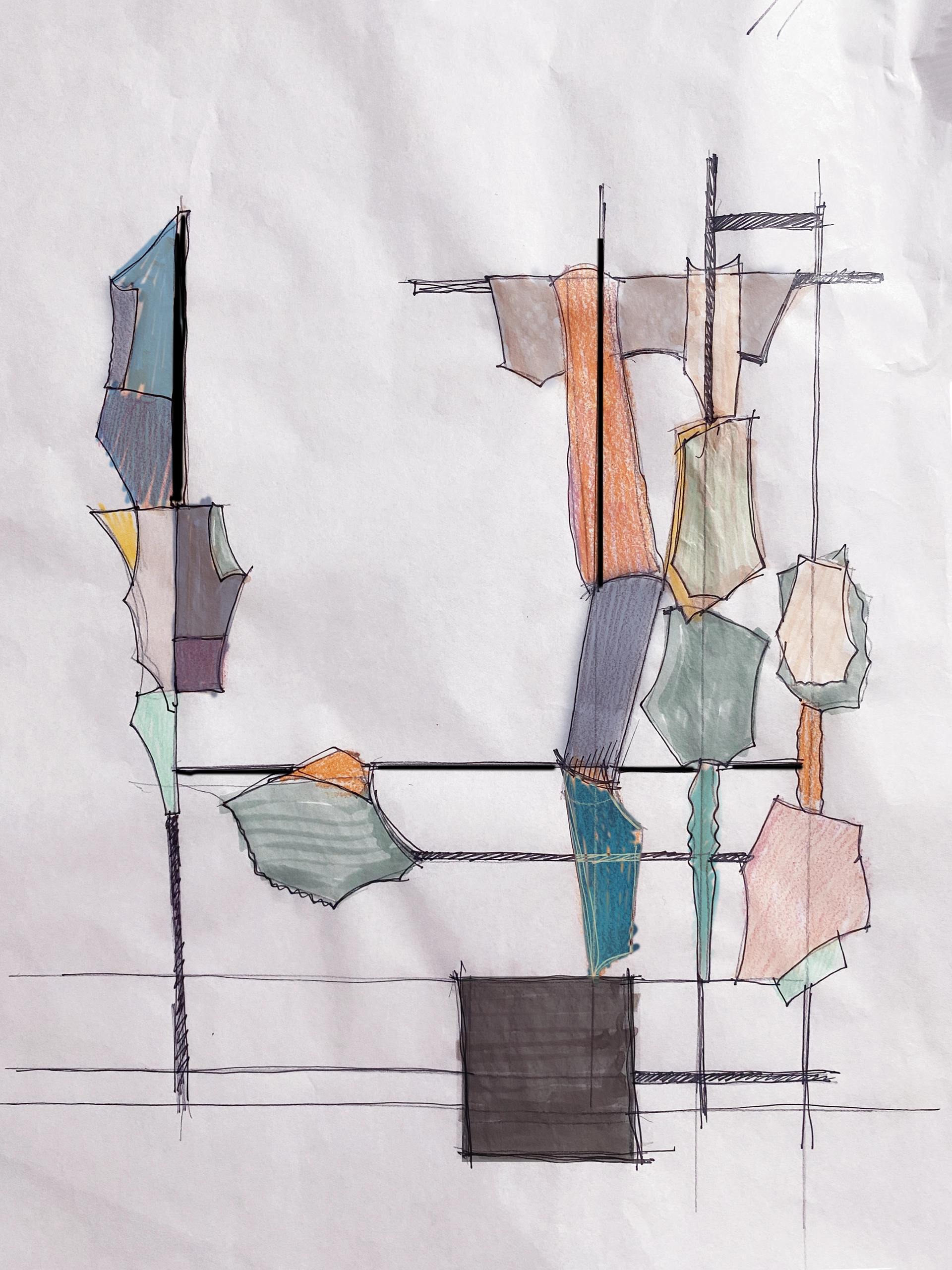

The transition from Maniera to Allegretto, the deformation you mention, happens right before the viewer’s eyes.

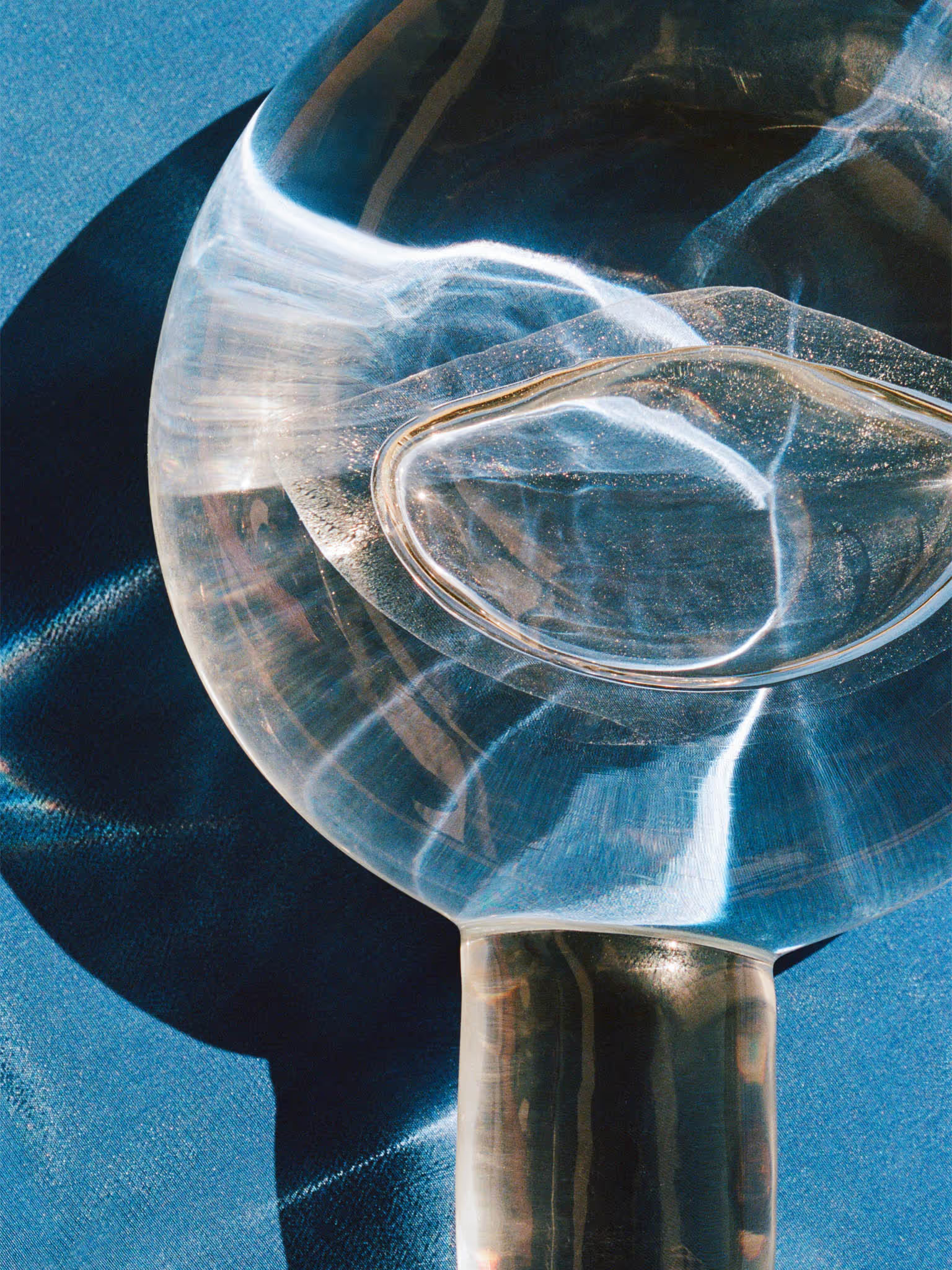

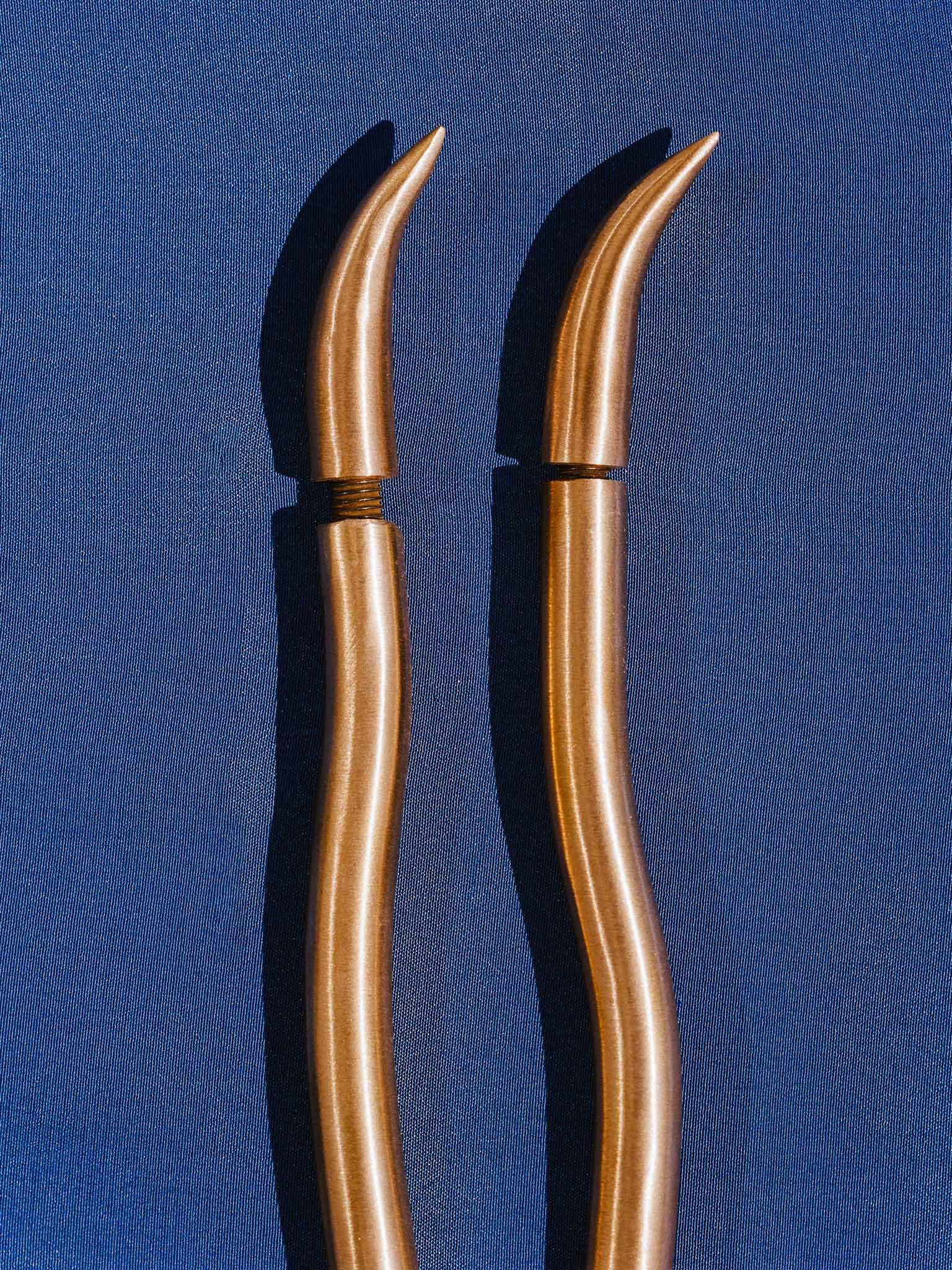

Exactly. Yes, exactly, we start with a wall that is 100% Maniera, and slowly the cladding begins to transform, as if it were being stripped, shifting, opening. There is a sense of unity, the material is the same, the approach shared, but at a certain point the lines are no longer straight, and only broken curves remain, like a treble clef, or some Baroque church plans. This gives the wall movement, not mechanical but poetic, heightened by the play of light on the surface. During the process, I described the wall as ‘sensual’, where sensuality comes from the material, from engaging all the senses, even though, as in all contemporary projects, the visual impact remains dominant.

How did the collaboration between you and Incalmi begin?

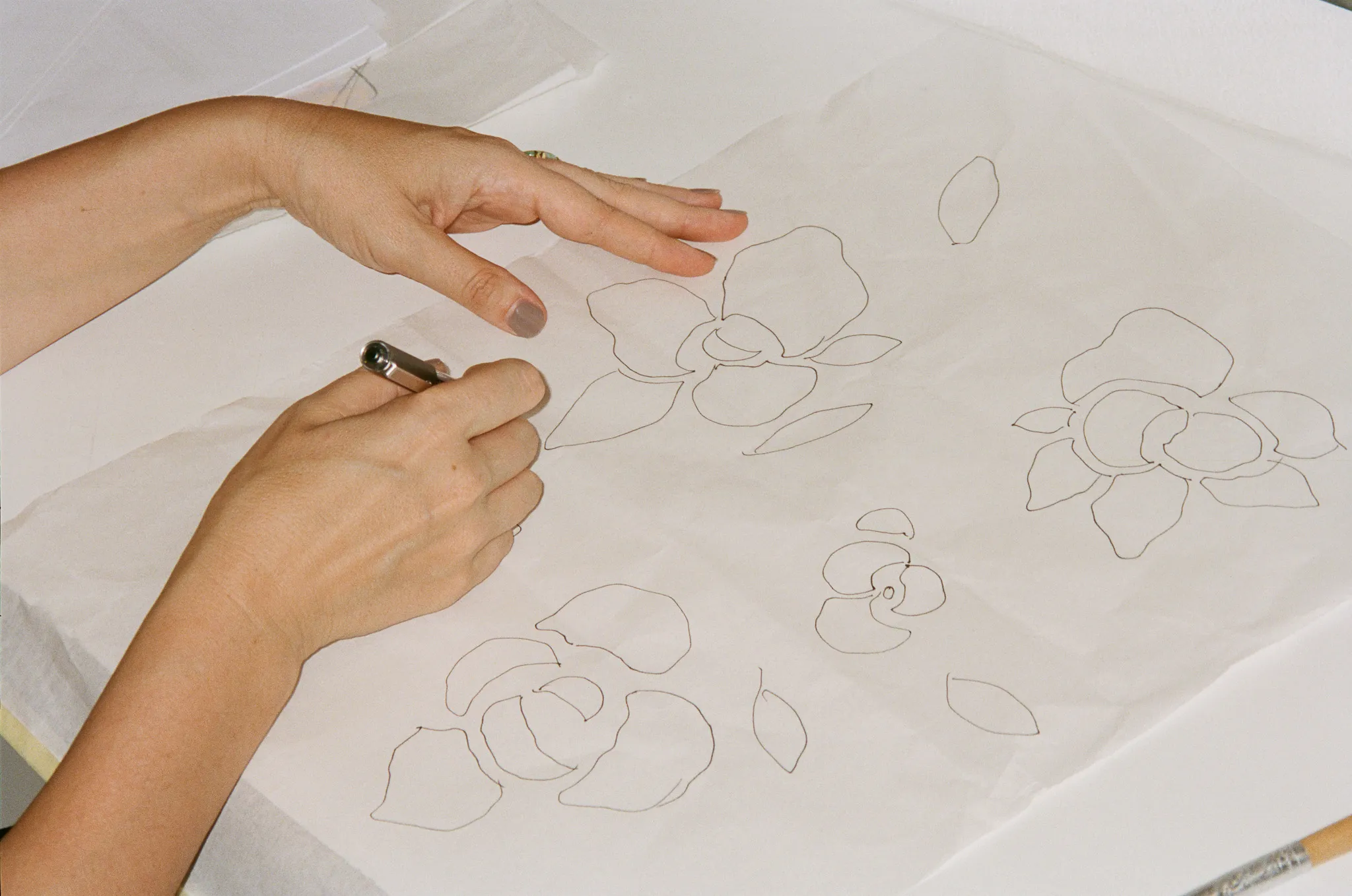

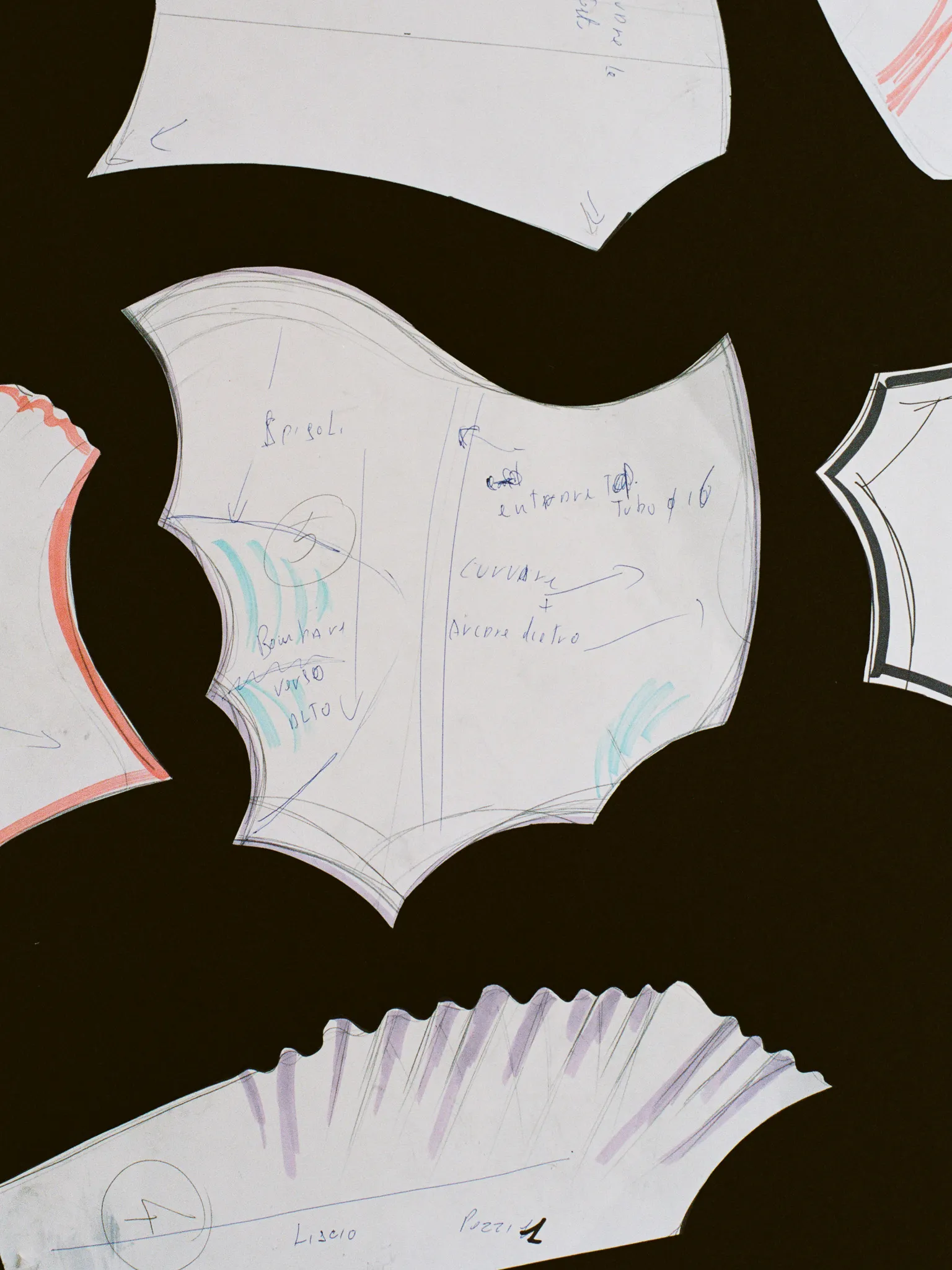

We met a few years ago while I was developing projects for an exhibition at the Jacqueline Sullivan Gallery in New York. I have a deep admiration for Fausto Melotti’s ceramic work, and I’m fascinated by the technique of enamel on copper, so I had the idea of combining the two. During my research, I discovered that Incalmi’s workshop was the only one working with this technique. We began collaborating, especially on my own projects. Later, it was they who invited me to work on this one.

How important was the location you were assigned, the former Santissima military hospital, in defining the project?

Very important. Starting from the space itself, I also envisioned the project’s visual impact, which is a natural approach in set design, one of my specialities. Having coordinates and constraints always helps me a lot: in this case, I chose to work around the two windows, cladding the space so as to incorporate the external landscape into the interior. It wasn’t conceived as a purely conceptual gesture; I simply worked on a corner of the room as if it were a section of a minimal space –minimal in the sense of reduced, not in the sense of minimalism.